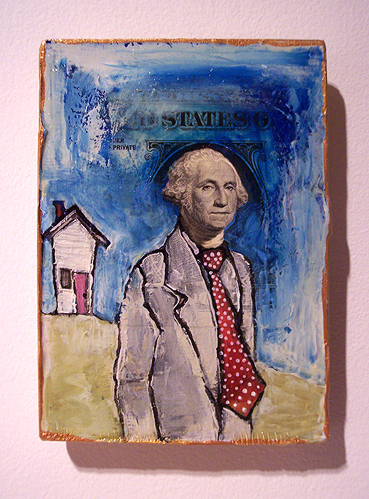

for bell hooks

vintage Americana, German pincushion dolls,

US currency, doll house furniture, women’s

polyester dress blouses, canvas, oil paint

85 x 75 x 9"

details:

in a small segregated black neighborhood in Hopkinsville, KY. She earned degrees at Stanford University

(B.A., 1973), the University of Wisconsin (M.A., 1976) and the University of California at Santa Cruz

(Ph.D., 1983). Her father was a janitor, her mother a maid who daily crossed the train tracks to work

in the homes of white families. To be on the margin is to be part of the whole but outside the main body. As black Americans living in

a small Kentucky town, the railroad tracks were a daily reminder of our marginality. Across those tracks

were paved streets, stores we could not enter, restaurants we could not eat in, and people we could not

look directly in the face. Across those tracks was a world we could work in as maids, as janitors, as

prostitutes, as long as it was in a service capacity. We could enter that world but we could not live

there. We had always to return to the margin, to cross the tracks, to shacks and abandoned houses on the

edge of town. There were laws to ensure our return. [Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center]

bell hooks—all lowercase letters—is a pseudonym chosen by Gloria Jean Watkins in remembrance of her famously

bell hooks—all lowercase letters—is a pseudonym chosen by Gloria Jean Watkins in remembrance of her famously sharp-tongued great grandmother. It affirms her chosen identity and vocation, brave truthteller, one who talks

back to authority, speaking truth to power in the tradition of the civil rights movement. I wasn’t sure I was brave enough to create this piece for this venue. After all: who am I? Only someone who

had the opportunity to make a piece so that the Kentucky writer of whom I am proudest is honored here. Who

has permission to speak to issues of race and class and sexism? And where do I get some? But bell hooks wrote

with no permission. There is no permission for poor black Kentucky girls to enter the academy and tell the

truth about what they find there. It quickly became obvious that the best way to honor hooks was to create

a piece that addresses the issues about which she cares.

The vintage artifacts—the delicate white princessy ceramic dolls, the sturdy ugly serviceable Aunt Jemimas—are

The vintage artifacts—the delicate white princessy ceramic dolls, the sturdy ugly serviceable Aunt Jemimas—are horrid. I hated to handle them; I hate to look at them. I hate what they signify. I used these artifacts because

they are the plainest possible way to present one aspect of the intersecting oppressions of race and class and

sex. In the current transition to a service economy, these combined oppressions are least noted and most ascendant.

Poor women of color are still free to throw their backs into the least secure, most poorly compensated, hazardous

and demeaning jobs our economy has to offer.

Classism, racism and sexism are as inherent in the white porcelain princesses as they are explicit in the aunt

Classism, racism and sexism are as inherent in the white porcelain princesses as they are explicit in the aunt Jemimas. It takes the hands of many, many poor women of color (these days, often unseen) to provide the requisite

products and services for even one middle class family.

I built for bell hooks in my living room, emptied out for the purpose. I did not feel I could responsibly construct

I built for bell hooks in my living room, emptied out for the purpose. I did not feel I could responsibly construct the piece in my public studio, for that context was insufficient to heighten awareness—not with the piece unfinished,

not with racist artifacts strewn about. I shudder to think anyone could relate to these artifacts as decoration. And,

of course, people do: that is exactly why these artifacts still exist and are sold in antique shops right alongside

carnival glass and bits of Wedgwood. When I paid the dealers for the syrup bottles and the paper towel dispenser, I

wanted to curse the money before I handed it over.

Aunt Jemima is the very icon and mandate from the haves to the have-nots, the image and script for poor women of color:

Aunt Jemima is the very icon and mandate from the haves to the have-nots, the image and script for poor women of color: this is how you will be valued, this is your value. Aunt Jemima is exactly that which a just society must shift, undermine,

explode, remake, iterate into something different and entirely new. I studied the works of every other artist I could

find who took on Aunt Jemima—particularly Bettye Saar—and I am aware of the risks of re-presenting the stereotype.

But, at least for me, Aunt Jemima wouldn’t move. The mechanisms in our society that resulted in Aunt Jemima kitsch

But, at least for me, Aunt Jemima wouldn’t move. The mechanisms in our society that resulted in Aunt Jemima kitsch still function as ever they did, even if other stereotyped images of poor black women have moved to the fore. So, in

for bell hooks, Aunt Jemima stands as I found her. I moved her from the margins to the center, and used her redoubled

form to point up to the question. The paired syrup bottles began to remind me of caryatids. And if you wish to wash your

hands of the struggle for liberation and justice, Aunt Jemima offers you a towel. Those who have not washed their hands can find clarity, strength and refuge in bell hooks’ books. She has published over

thirty of them, most recently (2007) a book of poetry.

The books are not always or predominantly intended for white readers. bell hooks chose to write to working-class black women.

Once mama said to me as I was about to go again to the predominantly white university, “You can take what the white

The books are not always or predominantly intended for white readers. bell hooks chose to write to working-class black women.

Once mama said to me as I was about to go again to the predominantly white university, “You can take what the whitepeople have to offer but you do not have to love them.” Now understanding her cultural codes I know that she was not

saying to me not to love people of other races. She was speaking about colonization and the reality of what it means

to be taught in a culture of domination by those who dominate. She was insisting on my power to be able to separate

useful knowledge that I might get from the dominating groups from participation in ways of knowing that would lead to

estrangement, alienation, and, worse, assimilation and cooption. She was saying that it is not necessary to give yourself

over to them to learn. Not having been in those institutions, she still knew that I might be faced again and again with

situations where I would be “tried,” made to feel as though a central requirement of my being accepted might be participation

in this system of exchange to ensure my success, my “making it.” [marginality as a site of resistance]

In for bell hooks I attempted to offer a different kind of trial. The piece is a test for myself and for its audience. Do I,

In for bell hooks I attempted to offer a different kind of trial. The piece is a test for myself and for its audience. Do I, do you, do we have the courage and willingness to speak to truth to power? When others do so, do we have the courage to listen?

home

home